This article originally appeared inthe February 2014 issueof Magazine as 4 Way to Make a Mortise.by Robert W. Lang

Pages 44-48

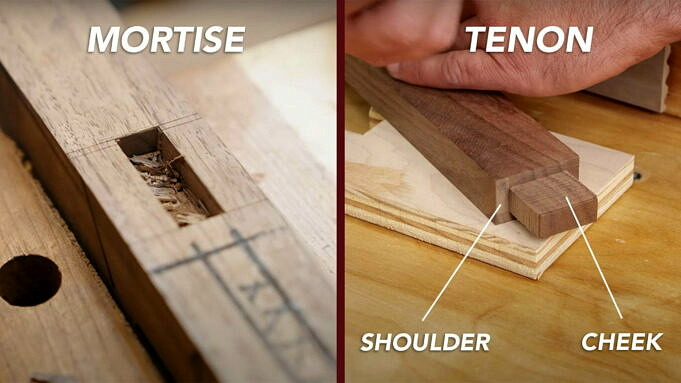

Woodworking is dominated by the mortise-and tenon joint. This joint, along with the dovetail has been in use for thousands of years. You might find it demanding and difficult judging by the many devices and methods that have been developed to prevent mortises. A mortise is a small hole in the wall.

It doesn’t matter how you dig the hole. It doesn’t matter if you cut by hand or use a machine to mill the material. This confusion is caused because it isn’t always easy to see what is essential in order for you make a solid joint in a reasonable time.

A mortise isnt any good without a matching tenon. The reason a joint fails is often because there is not enough wood around it. It is therefore sensible to allow the location and the size of your mortise to determine the size of your tenon.

The first thing to consider is where to locate the mortise too close to the end of a board leaves weak grain that can easily break while making the mortise, or when the finished joint is stressed.

The width and depth of the mortise are equally important. Plan a joint by not taking more than one-third of the mortised pieces’ thickness and making the mortise as deep or wide as possible. The depth of the mortised piece and the tenon are key factors in determining the strength of the joint.

Through-mortise-and-tenon joints are the strongest, but if you cant (or choose not to) go clear through, two-thirds the width of the mortised piece is a reasonable target.

That leaves the length of the mortise, or the width of the tenon to be determined. The tenon will be strongest the closer it is to the size of the piece on which it is made. Make the tenon as wide and thick as possible, and at least half as wide as the overall width of the workpiece.

What’s important, what’s not

There are five surfaces in a typical mortise. For the joint to function, two of these surfaces must be in perfect alignment. The rest don’t really matter.

You won’t be able to make a mortise that has a perfect bottom or ends. Worry instead about the wide cheeks and make sure they are straight and square, but dont bother to make them perfectly smooth. Extra space beyond the end of the tenon doesnt compromise joint strength and it leaves room for excess glue and bits of debris.

Unless you are making a through-mortise, extra space at the ends will let you adjust the position of the piece and easily take it apart after a test fit.

You can push a good joint together with hand pressure, and it will stay together when you lift the tenoned part.

Layout Rules

Whatever method you use to make your mortises, getting them the right size and in the right spot is critical. With machine methods, it is easy to set where the mortise lies in the thickness, and generally the width of the mortise matches the width of your tool, be it a drill bit, router bit or a chisel. If you aim for depth, it is easier than the tenon length,

Unless you are setting up for a large production run, it will likely take less time to mark all your mortises and work to your lines. Accepting that your ends don’t need to be perfect doesn’t mean you have to waste precious time setting up stops. Getting close by eye will be faster.

If at all possible, gang parts together and mark them as a group. Prepare a story stick and you need only to measure once. Knife lines and marking-gauge lines might take a little longer to make, but the payoff is in cutting the finished edges before you start to excavate and in providing a path for your tools to follow.

The Mighty Chisel

It has become a popular skill to demonstrate and write about chopping mortises entirely manually in recent years. Mortise chisels can be used to square up the ends of machine-made mortises. You’re still digging a hole, no matter how skilled or how good your shovel.

Making a mortise involves two steps: removing waste and cleaning up the edges. A mortise chisel’s mass is a big help. If the wood is soft, it can be hand-chopped in a very short time. If the wood or mortises are too hard, you’ll be in the same position as your ancestors, wishing for a quicker way.

There are two ways to use the chisel for cutting out mortise after marking the location. To create a V-shaped recess, make a cut in a middle area. This method requires some finesse to place the chisel to begin the cut.

The other method is to start near an end and make a series of cuts in one direction, then lever out the chips and repeat until you reach the desired depth. When the bulk of the waste is removed, drive the chisel straight down at the ends. You can prevent the chisel’s tilting from side to side by ensuring that it is straight.

If you are able to hold the chisel in your hand, it will stay straight. The chisel will stay vertical if the end at the business is square. If you place yourself behind the chisel you can see if it is leaning to one side or the other.

You can tell when the chisel has been driven to an optimal depth by the sound and by the amount of resistance you feel. To gain leverage, press against the bevel. The back and end scrape the sides while you remove the waste.

You can make a mortise with a mortise tool if you don’t have one. However, it takes a lot more patience. The process is essentially the same: Make a series of vertical cuts then lever out the waste. A standard chisel doesnt have the mass to go as deep with each cut.

No Shame in Using a Drill

If you look back in old books about woodworking technique, the use of a drill begins to be recommended right about the time that efficient drill bits became readily available. Again, the method you choose depends on the wood you are working with, the number of mortises you need to make and your desire to get the job done.

If your mission is to avoid the spouse and kids, get out your brace and bit and drill a hole to the depth of the mortise at one or both ends. This reduces the need to chopping. If you want to be productive, the more wood you can remove by drilling the better if you have an efficient and reliable way to power the drill.

Ideal for drilling is a drill press equipped with a fence, and a Forstner bits. It is possible to use a bit that is exactly the size of the mortise you are making, and then overlap the holes so they are vertical. This allows for easier chisel work, such as a few cuts at the ends and some paring of the side walls.

If you dont have a drill press, use a hand-held drill with a brad-point bit. Because you wont have the control youwould have with a stationary machine, use a bit that is – smaller than the width of the mortise. As with the chisel, the important thing is to keep the bit plumb side-to-side, and you can easily see that from the end of the mortise.

After drilling you need to pare the side walls with as wide a chisel as you can. If you marked the edges with a gauge or a knife, you will have a defined channel to locate the chisel. Paring is easier than you might think, especially if you excavated the holes with a drill press; all you need to do is shave off the high spots.

Router & Fence

In theory, the electric router is the ideal tool for making mortises. It is not if you are able to navigate the many jigs, complex methods and find a reliable and efficient method. However, most of the information you read makes it far more difficult than necessary.

With a plunge router equipped with a fence and an spiral-upcut bit, you have what you need and can get to work. Remember that the ends of a mortise do not need to be pretty and they do not need to be precisely located. What does need to be precise is the width (the

The bit’s diameter and its location (which is controlled by the fence). It is usually easier to take the router to work and see what you are doing, than to place the router on the router table.

If you can keep from tipping the router or biting off more than the router can chew, all you have to worry about is keeping the fence tight to the work. I always plunge the bit to the desired depth and then set the location by hand. The material is then discarded with subsequent passes that increase in depth.

There are limitations to the capabilities of the router. Mortises wide and 3 cm or so in depth can be made with a small router. Once that is complete, it’s time to switch to a big-boy router. This can be more difficult to control.

The spiral bit pulls the material out of the mortise as you go. The straight bit is able to grind the wood but the chunks and chips have no place to go.

Routers can also be used to make through-mortises on the sides of cases. To guide the bearing on a flush trim bit, it is easy to create a jig and achieve precise walls. To get the bit going (and to get rid of some waste), drill a hole and then square the corners.

Dedicated Mortiser

It is easy to believe that one machine can solve all your problems. At least, for a particular task. If you are making a lot mortises regularly, a hollow-chisel mortiser can be a cost-effective way to make mortises.

As discussed in Woodworking Essentials, November 2013 issue (#207), a benchtop machine will be able to do the job but it won’t take as long as a drill press or Forstner bits. The machine that has a moving table is more expensive. If you are willing to pay, the benefit is a quantum leap of productivity.

The performance of hollow-chisel mortisers suffers as the size of the bit and chisel increase. You can fit a or chisel in a benchtop machine, but a square contains four times the material as a square and a square has more than six times the area.

An inexpensive machine might breeze through or mortises but give up when you increase the size. You can make mortises larger than the chisel set by making multiple passes.

At the other end of the spectrum, hollow chisels and bits can be fragile. There isnt much metal you cant lean on a gardeners trowel the way you can on a spade. The good part of this is that in most cases you dont need to buy a complete set of bits.

The chisel/bit combination removes the waste and cuts the mortise sides cleanly in one step.

Most chisels benefit from a bit of sharpening. Make the outside smoother and touch up the inside with a diamond cone. Honing to fine grits makes the outside look nice, but doesnt add much benefit.

As the bit chews up the wood inside the mortise, the chips must move up through the chisel to escape. Allow enough space for the bit to move up the chisel. The bit may be too close to the machine, choking the exit route for waste.

The best practice for making mortises with a hollow-chisel machine is to make a series of square holes with a space in between. Once you have defined the mortise ends, go back through the process and remove any material. The bit and the chisel follow the path least resistance and bend in an open area next to the cut.

Adjust the Tenon

Mortises are straightforward to make, and if you dont get caught up in the minutiae of making them perfect at the ends or bottom, they dont take long to create. Adjusting the size of a completed mortise is another story youre trying to make fine adjustments inside a narrow hole.

Tenons are easier to adjust because you can see what is happening and have access the work. If your skills in mortising make the size unpredictable, wait and cut your tenons to fit. Start by measuring a slightly larger tenon and then adjust until it fits properly.

– Robert W. Lang